Implications of Navy Cost Estimating Theater

“The first principle is that you must not fool yourself—and you are the easiest person to fool.” - Richard Feynman

Introduction

In my five previous posts describing what I have called Cost Estimating Theater, I discussed why bottom-up cost and schedule estimates for new projects like warship construction are never accurate don’t work out. I have likened cost estimating to theater because, like theater, there are many speeches and performances on the public stage that have no connection to reality.

I close my series on Cost Estimating Theatre with a review of the Planning Fallacy, thoughts on whether accepting it is pragmatic or depressing, the reasonableness of expecting to “bend the cost curve,” and the implications for the U.S. Navy of predictably inaccurate estimates of cost and schedule for major projects.

Review of the Planning Fallacy

Bottom-up estimates for complex projects, while intuitively appealing, are based on imagined sequences of activities. No one imagines material delays, work stoppages, labor shortages, impacts of poor design, strikes, test failures, hurricanes, and COVID-19 (Lagrone, 2024) affecting their project. That’s probably a good thing or they would never sleep at night. Although any of these delay factors might be improbable, history suggests that some will certainly impact the schedule. Project prediction errors result from an internal focus that underweights the distribution of past projects and overweights senior leader’s conviction that “this time, we’ll get it right.”

Independent cost estimates are sometimes cited as reasons to have confidence in predictions. Independence has an air of rationality like medical second opinions or academic peer reviews. They aren’t a remedy for the Planning Fallacy since they suffer from the same misplaced confidence in bottom up work sequences (Kahneman&Tversky, 1977). Assessments of the “reasonableness” of predicted outcomes of planned work sequences shouldn’t make you more confident, especially when the assessors don’t have experience doing the work.

The external approach to forecasting using distributional information recommended by Kahneman and Tversky requires project managers to ask, “How long do similar projects last and what do they cost?” I was confronted with this situation three times in my career. Three times I worked for leaders who insisted that my warnings of higher cost and late delivery were wrong. Twice I used distributional data to convince them that the embarrassment suffered by accepting my recommendations would be lower than going over a cliff Thelma and Louise style with the original plan. I wasn’t successful in the third case even with reference class data, but there were other factors involved.

Pragmatic or Depressing?

At one level, accepting that using repeat designs and having conversations with shipyard leaders will make NO difference in ship cost is pragmatic and sensible. One might think that engineers, cost analysts, and budgeteers, job titles that function like magnets for the grave and humorless people who insist on proof with data, would embrace it. People in these professions are not easily fooled, recognize and understand bell curves, and look askance at efforts to build bridges with origami paper no matter how well folded.

On another level, believing that you are not special, probably aren’t an above-average math student (Kruger & Dunning, 1999), and your ship is going to cost more to build than you hope is profoundly unsettling. No one wants to live in an unpredictable world. The problem is that things like steel plates, hull sections, piping, electronic wiring, computer programs, forming and joining processes, and computer control systems don’t care how hard anyone tries. Expecting that any shipyard and design agency can build a survivable warship with Ferrari-like capabilities while simultaneously “bending the cost curve” is to believe that Elvis isn’t dead unreasonable.

Bending the Cost Curve, Really?

One criticism I’ve received from readers, bless them, is that the Planning Fallacy is too pessimistic. Some claim that it must be possible to do super innovative, but unspecified things to reduce warship costs. It absolutely is: build simpler ships, don’t outfit them with state-of-the-art anything, and use fewer people to construct them. This isn’t magic, just manufacturing pragmatism. This approach was used to build 2,710 Liberty ships across six shipyards in the U.S. between 1941 and 1945. Our adversaries ran out of submarines before we ran out of cargo ships.

At its heart, the Planning Fallacy is a recognition that outcomes of the processes and human performance involved in warship construction are normally distributed. The majority (68%) of new warship cost/ton are going to be within one standard deviation of the mean for ships with similar characteristics.

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) has acknowledged that a limitation of using historical data to estimate the cost per ton of new designs is that it doesn’t benefit from recent improvements in shipbuilding processes and new technologies that might lower costs (2018). At the same time, CBO has further noted that they have never seen a new ship design cost less per ton than previous, similar ships. Never.

The consequence of believing that manufacturing and construction outcomes for ships are normally distributed is that innovation options are limited. The burden falls upon the We’ll-Bend-The-Cost-Curve crowd to explain exactly how they’ll do it. Which new technologies will reduce cost and how have they worked when tried? Which design approaches to Combat Systems software will make the code shorter and simpler to test? How do you know? If you can’t be specific about how you’ll reduce costs and lack the data to demonstrate why others should believe you, you’re just writing a script for Cost Analysis Theater (Verschuere&Meijer, 2023).

What Does This Mean?

I didn’t write these blog posts about Cost Estimating Theater to criticize Navy practices for estimating cost and schedule for new warship classes. Institutional incentives for warship construction do not prioritize accurate cost and schedule predictions. The reality is that there aren’t personal consequences for inaccurate warship construction estimates so current practices will likely continue.

One way to think about straight-faced expressions of confidence in ship construction estimates despite the Planning Fallacy is that they represent an organizational myth deeply held (Meyer & Rowan, 1977). Myths, institutionalized beliefs and ideas that are taken for granted, abound in organizations. They are a powerful source of legitimation that provides support for the Navy’s claim on specific missions and roles in the national defense. Strongly espoused support for uncertain cost and schedule projections and other myths (like the nuclear triad) provide legitimacy for those claims.

Senior leaders in the DOD have demonstrated by word and deed that accurate predictions for lifecycle costs (construction and subsequent maintenance) aren’t as important as the on-paper capability of its platforms. Members of Congress on the relevant committees don’t object very strongly. Invoking experience from WW2 merchant ship acquisition programs won’t change this. I just thought it was an interesting example.

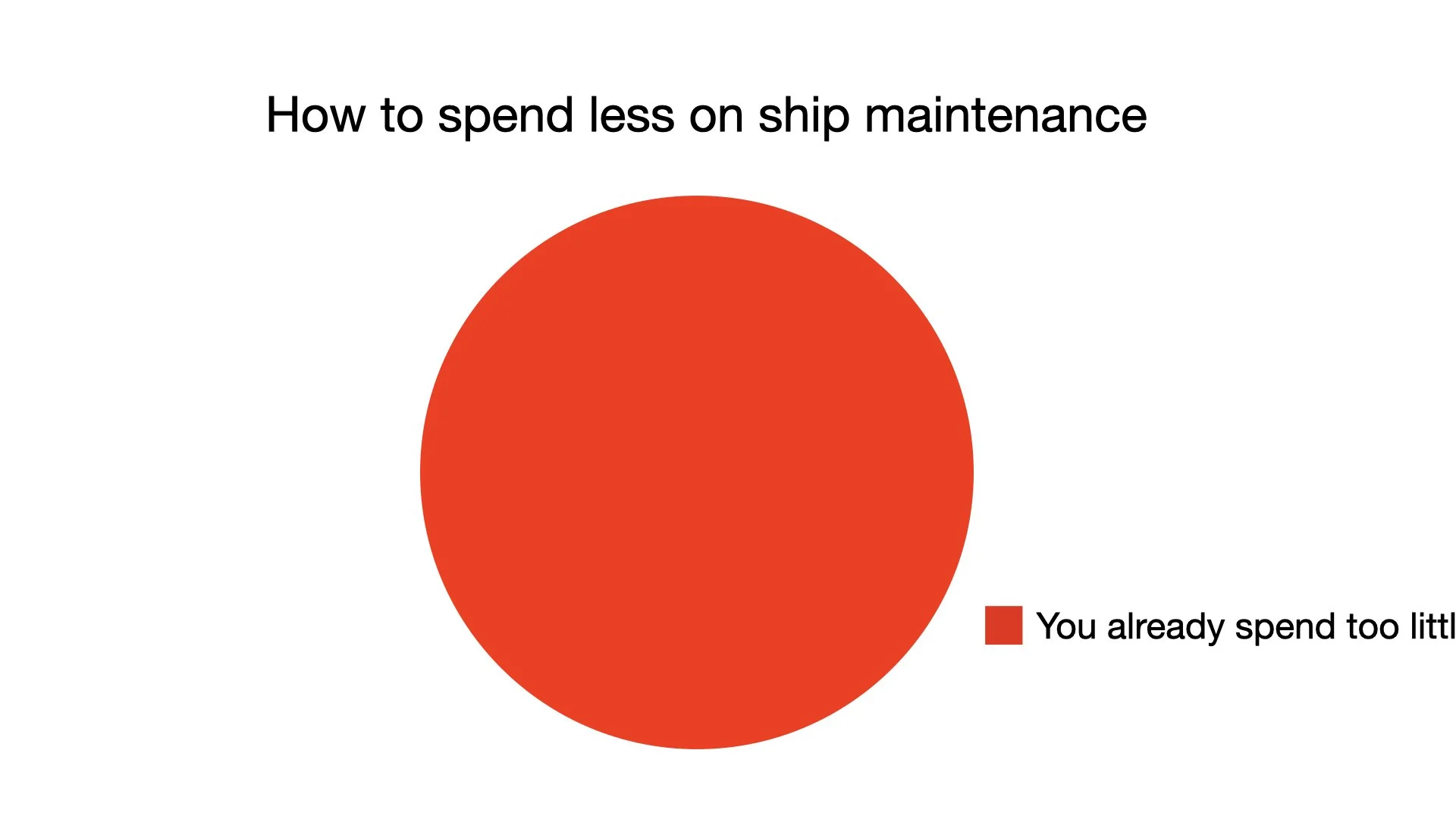

The fiscal reality is that acquisition program cost growth does not generate automatic increases to the Navy’s budget. People who argue that the Navy doesn’t buy enough ships and shipyard parking garages or fund maintenance adequately might consider this before complaining that members of Congress just don’t understand. Maybe they do.

Note: new references have been added to the references for the first post in the series.